Toulouse-Lautrec

Toulouse-Lautrec

Born in 1864 into a distinguished aristocratic family that traced its roots to medieval times, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901) struck success in 1891 with his first poster, Moulin Rouge, La Goulue. He left behind a large number of diverse prints and oil paintings created using lithographic techniques that he learned in the course of producing posters. However, he is remembered almost exclusively as a poster artist. Even after his death, French national and public museums did not accept his oil paintings. During the period of Lautrec’s “absence” from art history, the person most responsible for paving the way to the worldwide appreciation of Lautrec’s entire artistic output was his friend and art dealer Maurice Joyant (1864-1930). Working with Lautrec’s family, he was instrumental both in donating Lautrec’s prints to the Bibliothèque nationale de France in 1902 and in the opening the Musée Toulouse-Lautrec in Albi in 1922.

The collection of works by Toulouse-Lautrec held by the Mitsubishi Ichigokan Museum, Tokyo (MIMT) features 32 posters from the Maurice Joyant Collection, which has preserved the artist’s legacy, including different versions of the same poster. It also comprises major lithographic prints, such as two impressions of Miss Loïe Fuller (1893), and a collection of representative prints including Le Café Concert (1893), produced in collaboration with Henri-Gabriel Ibels (1867–1914), and Elles (1897). The 136 prints on show in this exhibition include all of these works along with 11 pieces on loan from the Bibliothèque nationale de France. We hope that the exhibition challenges us to reconsider the works of Lautrec, the great chronicler of his times, from the perspective of absence and its flip side, presence.

I

Presence and absence in connection with Lautrec

The focus here is on the models and friends whose presence was recorded by the artist. These figures include Picasso, who was quick to pay attention to Lautrec’s work even during his lifetime, and Joyant, who steadfastly preserved Lautrec’s work during the artist’s “absence.”

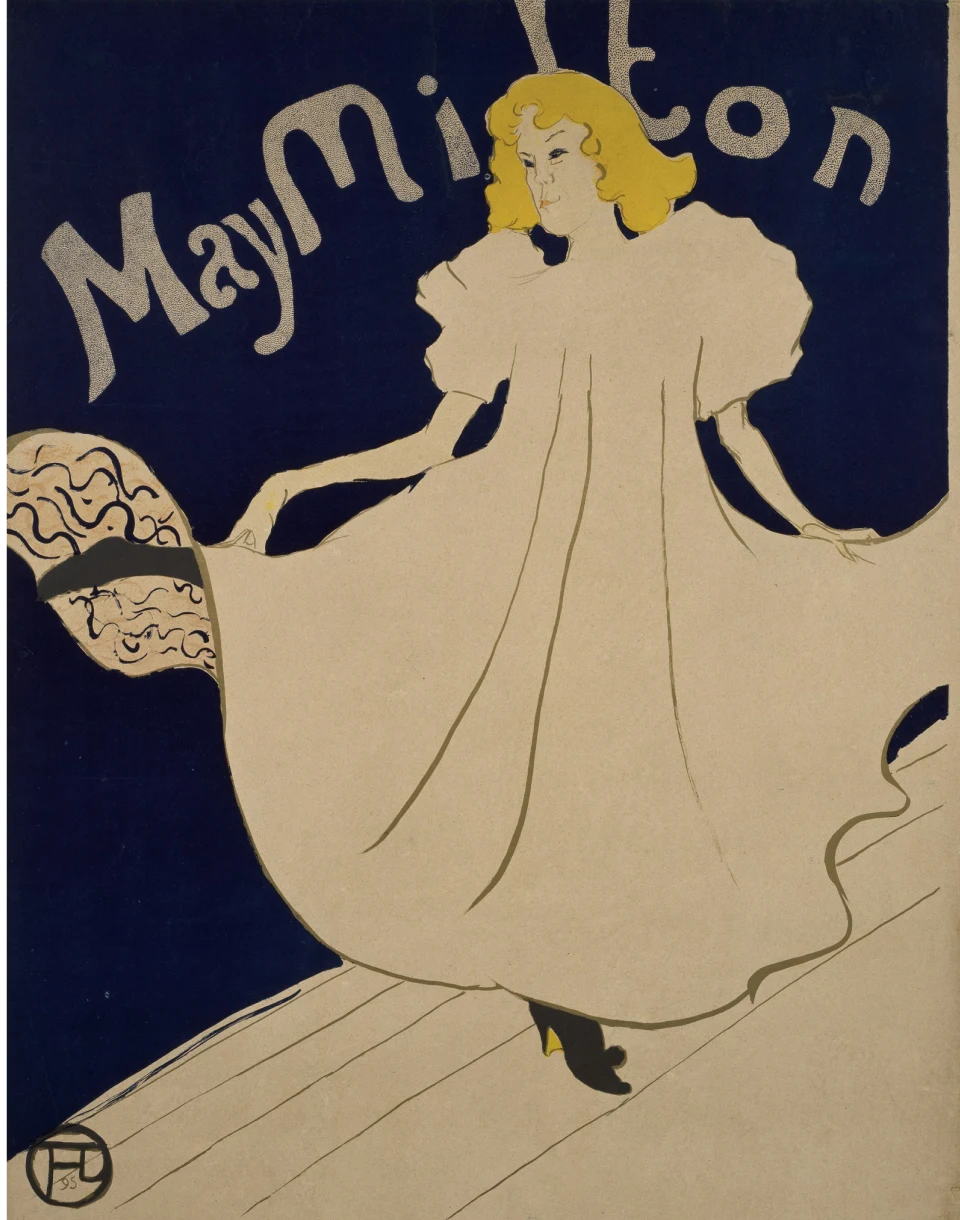

Picasso was one of a number of painters who were captivated by Lautrec’s work before he died. Inspired by Lautrec, Picasso took up subjects such as circuses and the marginalized poor of society. As a homage to Lautrec, shortly before the French artist’s death, Picasso even incorporated a copy of Lautrec’s poster May Milton (1895) in his painting The Blue Room (1901, The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.).

While dancer May Milton’s name can be found in some newspaper and magazine articles of the time, there are otherwise very few remaining records of her presence; just these articles, this poster by Lautrec, and a few sketches.

Before his death, Lautrec presented Joyant with a work bearing a dedication, as a testament of the friendship he felt. As an animal to represent Joyant, the artist chose a crocodile. The back cover of Histoires Naturelles (Natural History) by Jules Renard features a crocodile with a dedication by the artist.

II

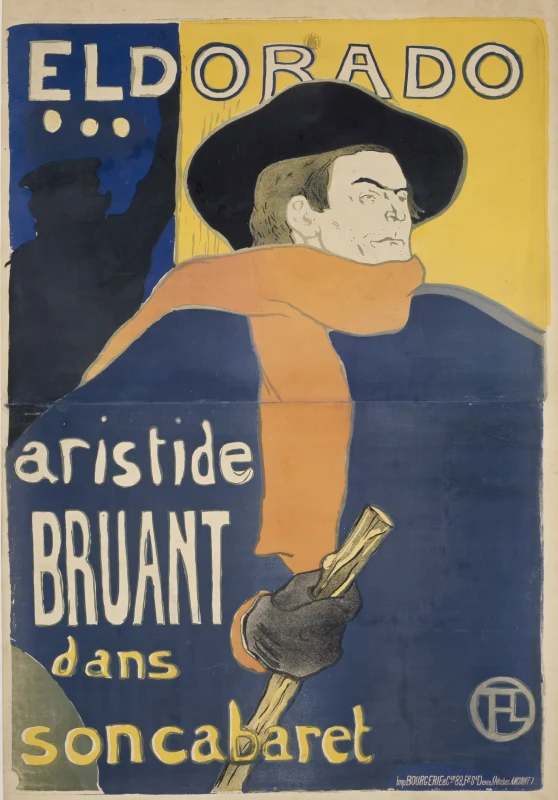

Emphasis by “repetition”: the scarf of Bruant and hat of Avril

Lautrec highlighted the individuality of his models by drawing them repeatedly, not only depicting their facial features, hairstyle, and physique, but also representing them by their clothing, or the props they used. Like this, he imprinted their presence in people’s minds. In the case of Aristide Bruant, Lautrec focused on the singer’s scarf, making repeated use of it; in the case Jane Avri, he used the dancer’s hat as a distinguishing motif. Bruant also purchased oil paintings from Lautrec and commissioned him to make posters, helping the artist to achieve success in Montmartre. Avril also rated the Lautrec’s talent highly, ordering posters from him.

III

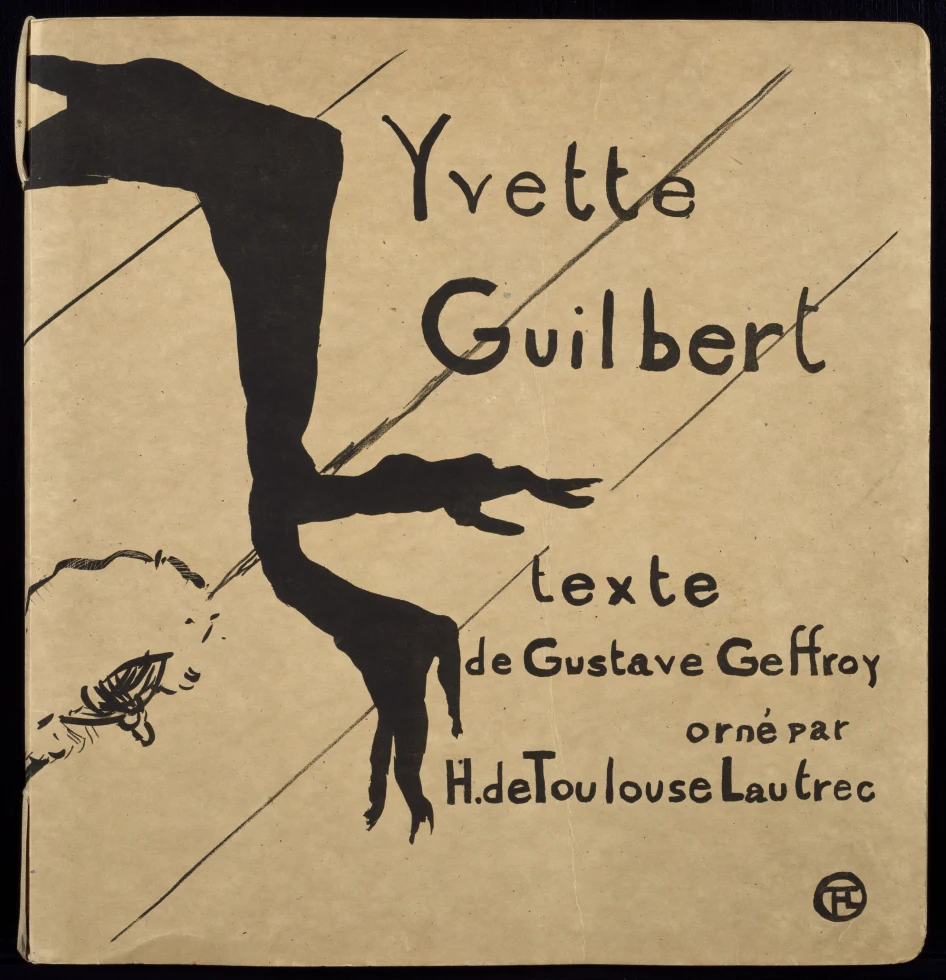

Making absence and presence visible: posters and Gilbert’s long black gloves

The people that Lautrec depicted are long gone and largely forgotten today, yet they live on in the artist’s posters. He accentuated the presence of his models by emphasizing their unique features, like the portly physique of comic Caudieux and the long gloves that singer Yvette Guilbert typically wore on stage. In the poster Divan Japonais, the lady escorted by the gentleman is clearly identifiable as Jane Avril by her hat. Similarly, by her gloves, the singer on stage, whose face is nondescript, is unmistakably Guilbert. In Lautrec’s Album Yvette Gilbert, Cover, which only shows the singer’s gloves, the singer’s presence is strongly asserted despite her absence.

IV

The absence of color and the presence of line drawings

Lautrec’s posters were finished as vividly colored polychrome prints, but the Maurice Joyant Collection also contains many monochrome prints. Lautrec contributed many illustrations to Le Café Concert and other publications at a time when most illustrations were printed in monochrome. Absent of color, the trial prints and illustrations for these posters obviously lack the presence they would have if overlaid with color plates, but Lautrec’s richly expressive lines still assert a certain power.

V

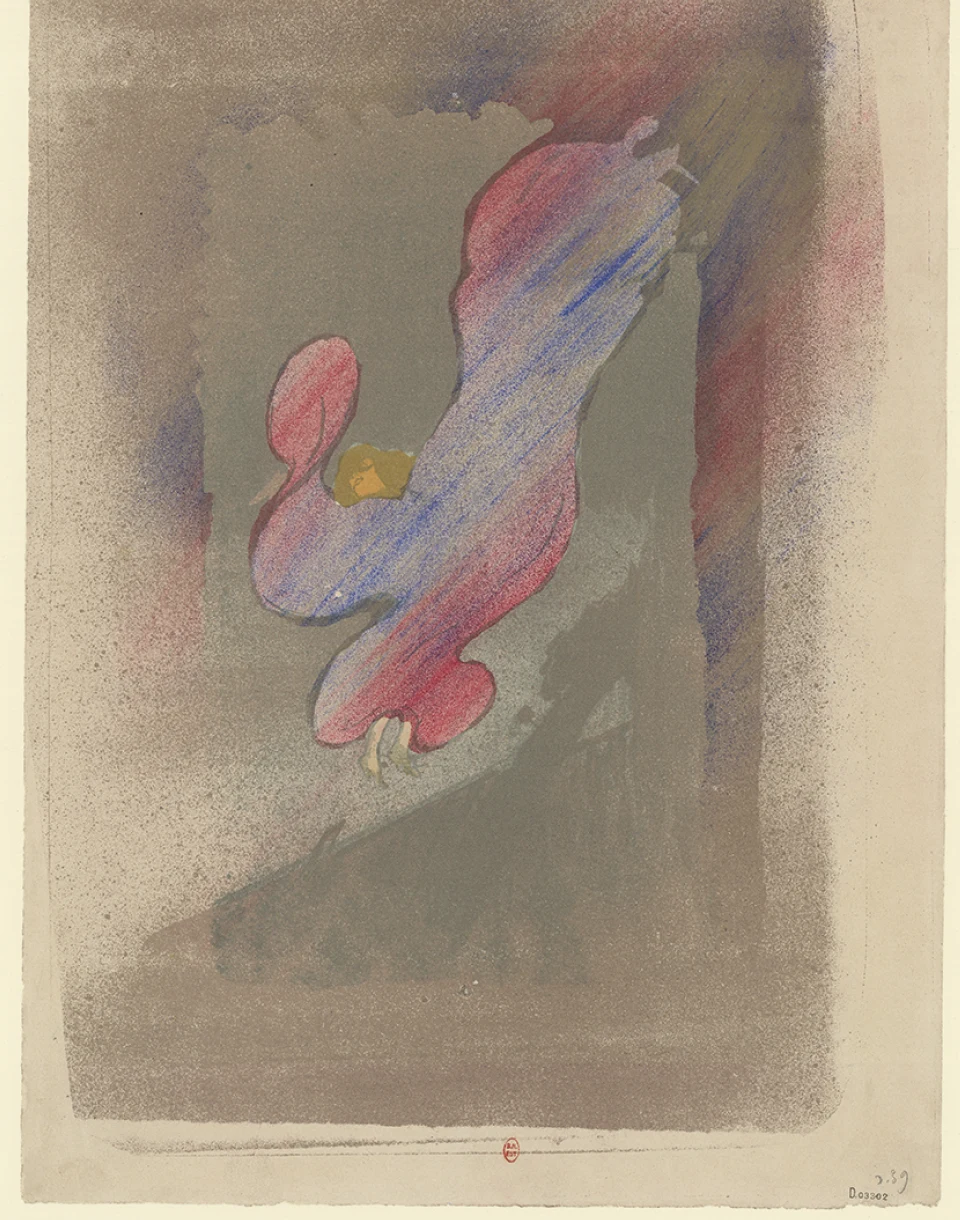

Absence of form

Loïe Fuller, a dancer from the United States, attracted much public attention with her striking stage performances, in which light of changing colors was skillfully projected onto her white costume as she danced. When Lautrec depicted the dancer, he concentrated not on her facial expressions, the shape of her costume, or other specific forms, but rather on the shifting of these colors, one at a time.

VI

Absence of text presence of women and absence of men

The set of lithographs Elles takes the form of a portfolio, with the works inserted between two folded covers. Here, Lautrec tries to express the diversity of women’s presence without the aid of words (text).

In the process of creating Elles, Lautrec made sketches in a low-class brothel, intending his work for the enjoyment of men. Yet, no male figure appears in any of the works. Thus, this collection of prints also makes a statement about the relationship between absence and presence.